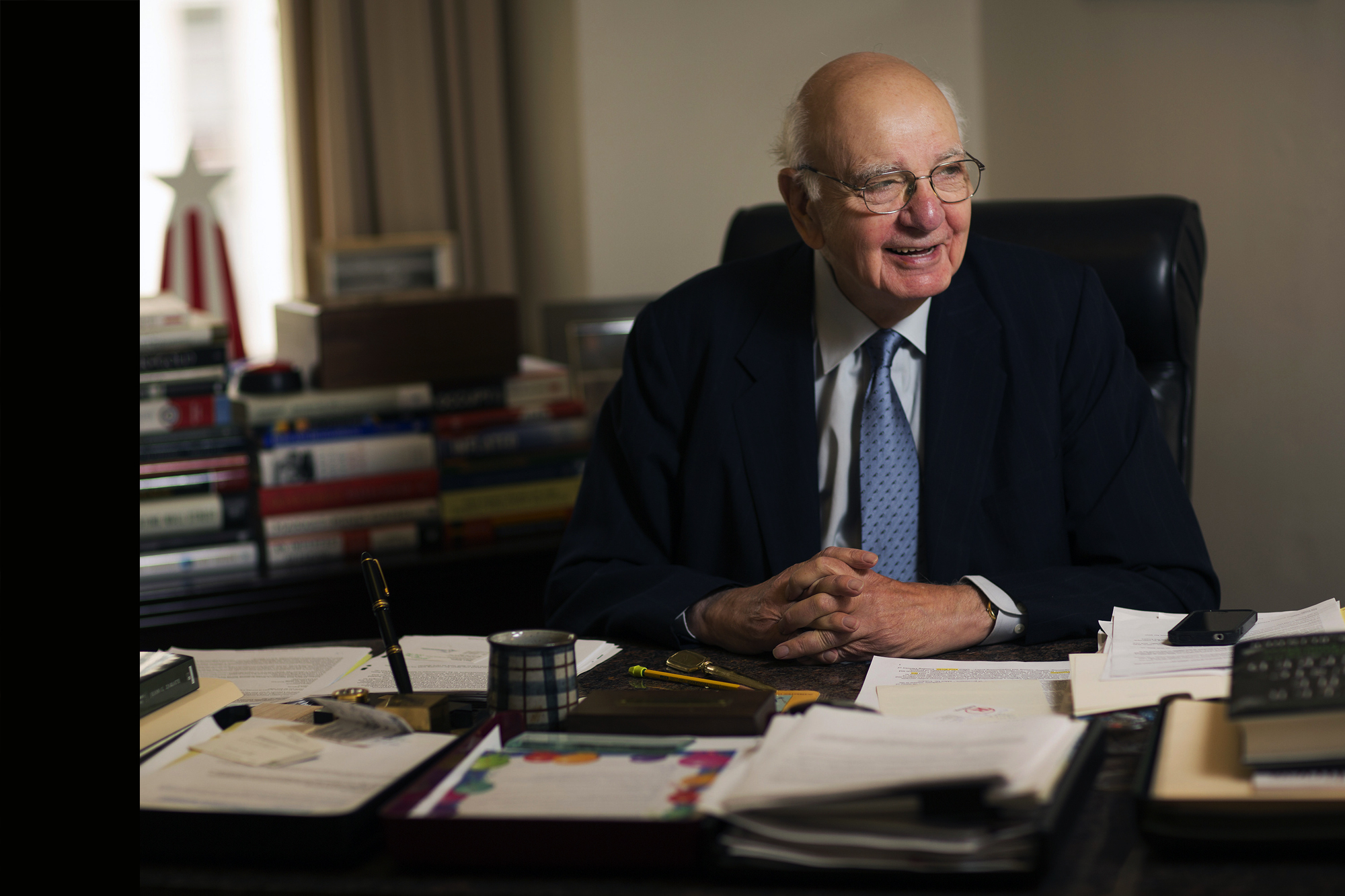

IN THE MEDIA: Paul Volcker and the End of Inflation as Our Parents Knew It

Photo: Paul Volcker by Robert Caplin/NYT/Redux/laif

His last name was often misspelled until the end, and many people will probably never understand what he did for them, their world, and above all, for their savings: Paul Volcker. Last Sunday, after a public career spanning seven decades as “inflation’s worst enemy,” he passed away at the age of 92.

As William L. Silber puts it in his 2012 biography of the economist, Volcker’s greatest achievement was becoming Federal Reserve chairman in 1979 and taming chronic inflation. Even though the situation in the USA on the threshold to the 1980s was completely different from what it is today (13% inflation instead of 1,8% today), the same means were used to fight a two-pronged war against inflation on the one hand and recession on the other. Volcker applied his own ideas to battling inflation: Despite opposition, he raised interest rates. Criticism poured in from all sides of the economic and political spectrum. In 1980, bank interest rates skyrocketed to 20%, drastically cutting consumer spending, while inflation hit 15%. The money supply fell, but Volcker’s attack on inflation proved useful. It dropped from 12% in 1980 all the way to 4% by the end of 1981.

Since then, it has never risen above 6% again – which proved to be particularly beneficial for savers and has made his intervention a textbook example of effective monetary policy to this day. Volcker ran as FED chairman a second time, then, in 1987, he declined a third appointment and decided to make some money – finally, because the FED job wasn’t well paid – as chairman of a private investment firm, which he took public in 1996.

But nothing really tempered his devotion to public service: in 2008, he endorsed and then advised Democratic presidential candidate Barack Obama. After his election, Volcker headed the President’s Economic Recovery Advisory Board and championed the regulation that Obama offhandedly named the “Volcker Rule” (which is part of the Dodd-Frank Act, introduced in 2010). It says that a bank that has recourse to government support can’t engage in trading for its own account or have a stake in hedge funds or private equity funds. Though there are concerns that the Volcker Rule may result in curbing liquidity in the bond market in times of stress, or that – in a market economy – market participants, not regulators, should monitor banks, the overall results of the rule (and its public appreciation) are quite positive.

Next Steps

Take a look at getAbstract’s related channels such as Economic History, Crisis Management, and The Role of Government in Economics. Or take a look at our summaries and reviews of publications of the Federal Reserve Board.